Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Frolic examined

Brandywine River Museum's 'The Way Back: The Paintings of George A. Weymouth'

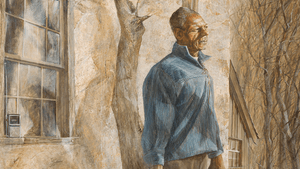

You might be tempted to miss — or dismiss — the artwork of George A. “Frolic” Weymouth (1936–2016), whose work is currently on display in The Way Back: The Paintings of George A. Weymouth, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art. Not well known outside the region, he was committed to land conservancy, equestrian prowess, and a bon vivant lifestyle that often eclipsed his art.

There’s his similarity — on first glance — to Andrew Wyeth, who encouraged and influenced the younger man. Both looked to and into the region for grounding and inspiration. Both reveled in detail, working in the exacting media of tempera and watercolor, and both were master draftsmen.

They shared a mutual respect and sometimes even a color palette. But The Way Back makes clear that Weymouth possessed a deep, lifelong artistic practice (the first work here was painted at age 12) and a view that is his own.

Friends and family

Joseph J. Rishel — a curator emeritus of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Frolic’s friend — was guest curator. The exhibition is mounted in jewel-toned galleries by coordinating curator Audrey Lewis. Artworks were culled from museums (including the Brandywine) and rarely seen private collections.

The 65 works are about evenly divided between landscapes and portraits, with a few animal and genre paintings and — one of the surprises of the exhibition — the artist’s sensitive drawings.

Weymouth’s large-scale portraits, often of family or friends and seldom created on commission, reflect a sympathetic psychological eye. In a film at the exhibition’s entrance, the artist says, “The person is so much more important than your painting of them.”

Next to many works, the museum has adroitly placed compositional “sketches.” Some are preparatory, but others are fully rendered, very fine watercolors.

It’s clear Weymouth was a master of that medium, filling his frames with movement and an often vibrant palette. One of the most evocative is Jack Campbell’s Coat, depicting a hanging blue jean jacket that evokes the wearer’s presence by his absence and makes denim as elegant as velvet.

It’s a surprise to see that watercolors are sketches for Weymouth’s large-scale works in tempera, another exacting medium that places very different demands on the artist. The contrast between the fluid Study for August and the minute detail of the much larger tempera August — probably the artist’s best-known work — is especially revealing.

In portraits, the sitter’s expression and pose are often modified as Weymouth works in differing media. In Gathering Storm, a finely drawn pencil study shows a woman apprehensive about what is to come, while the finished tempera shows her petulantly resigned to fate.

Large-scale detail

Some works — both portraits and landscapes — evidence Frolic’s trademark wit. In Eugene Eleuthere duPont, a bulky stone pillar cleverly echoes the man. Website makes a wry comment on our connected world with spiderwebs, and Night Life has flowers dancing up a storm on a dark evening.

Weymouth studied art at Yale, choosing realism over the Albers-led abstraction prevalent there, yet he has a soupçon of the avant-garde. In portraits, the artist uses abstraction or opaque backgrounds to contrast with his extreme detail. Melanie in Repose (a loving portrait of a favorite dog) and The Earl of Westmoreland, Master of the Horse (depicting a self-important nobleman) show this to great effect.

It’s striking to see the way Weymouth manipulates and transposes scale and scope. Over and over, he paints large-scale images but telescopes the emotional or narrative center of the work into a miniature.

In Eleven O’Clock News, a man is mysteriously focused, listening to a barely visible transistor radio in the painting’s corner. In Robin’s House, the entire work is filled with swaths of empty, snowy hills, the tiny far-distant house a striking portrait of desolation.

Weymouth was an avid horseman — he captained the Yale polo team to a victory in Britain — yet he seldom painted horses. One exception is The Way Back, a large tempera (with two elegant studies) that is the exhibition’s signature image. Holding the reins, a driver — seated behind the horse — heads for a stone house framed by winter trees. It’s a complex image rendered in warm colors, yet with a touch of bleakness.

In one section of the film, Weymouth makes egg tempera — a slow and delicate process — rolling the yolk in his hands and showing how the yellow slowly disappears into the color as he adds it. It’s a fitting metaphor for the work of this artist, private and full of contrasts, whose art has (until now) tended to disappear into his life.

What, When, Where

The Way Back: The Paintings of George A. Weymouth. Through June 3, 2018, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, One Hoffman's Mill Road, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. (610) 388-2700 or brandywine.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder