Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Getting on the bus

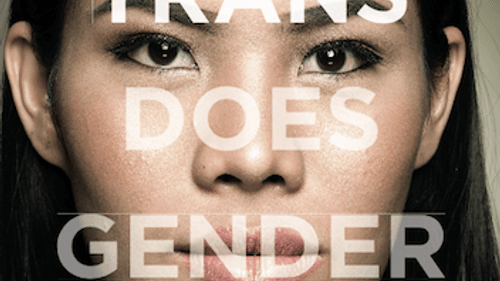

'Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter?' by Heath Fogg Davis

One day in 2007, a transgender African-American woman named Charlene Arcila tried to use her monthly SEPTA Transpass — marked with an F for "female" — only to be challenged by a bus driver who claimed the pass was invalid because, as he said, “You are not a female.”

Arcila wearily returned to the front of the bus and fed two dollars into the meter. She also filed a legal complaint with the city, alleging that SEPTA’s sex-sticker policy, instituted in 1981 as a fraud-prevention tactic, violated her civil right to be free of gender identity discrimination.

While the legal challenge is still in limbo, SEPTA quietly ceased the sex-sticker policy in 2013. For Heath Fogg Davis, an associate professor of political science at Temple University, the story is a painful illustration of the harm caused when public and private institutions — departments of vital records, schools and colleges, amateur and professional athletic associations — try to classify people by sex.

M, F, or nah?

In Beyond Trans: Does Gender Matter? Davis builds a thoughtful argument that, for bureaucratic purposes, gender should matter a lot less than it currently does. Using four case studies, he explains why those who oversee identity documents, restrooms, universities, and sports teams should do what SEPTA did—that is, expunge the M and F stickers or their equivalents.

Davis’s argument is so deftly constructed, his tone so reasonable, it’s easy to forget he’s proposing a tectonic shift in how U.S. organizations, from the Little League to the Department of Motor Vehicles, think of sex and gender identity. “I believe that all of us would be better off in a society with dramatically fewer sex-classification policies,” he writes. “And I argue that the basic structure of antidiscrimination law can help us make this happen.”

Davis makes an important distinction between sexism — judgments about what people can or cannot do because they are male or female — and sex-identity discrimination, or assessments of whether a person belongs to the categories of male or female. It was sex-identity discrimination, he says, that nearly got Arcila booted off the bus (and, he notes, it didn’t help when she later obtained a “male” SEPTA pass; a driver rejected that one, too, because she didn’t look male).

He also notes that sex-identity discrimination hurts us all — not just trans or genderfluid people but also butch women and femme boys, anyone whose appearance, behavior, or self-concept doesn’t match conventional, gendered norms. Sex-classification "policies constrict everyone’s personal freedom to imagine and define not just our gender expression… but also our authority to make self-regarding decisions about our sex identities — about who we are in relation to the categories of male and female,” Davis writes.

Seeing privilege from all sides

He speaks from experience. As a transgender man who transitioned at 38 — and who, prior to transitioning, preferred boys’ clothes and short hair — Davis has been chided by girls and women for using the “wrong” bathroom. He writes of his unease with the privilege he now bears, in “men’s” restrooms and elsewhere, as a trans man who cleaves to expected male standards of dress, hairstyle, and behavior.

Davis isn’t urging a deluge of lawsuits to undo decades of sex classification; he’d prefer to see organizations proactively evaluate the ways sex identification figures into employee handbooks, restroom designation, recruitment, hiring, and health insurance, then question whether practices that label people “men” and “women” truly fulfill the group’s policy goals.

He’d also like those organizations to be more inclusive and transparent. If a health center's intake form has a check-off box for “male/female,” that form should explain why the information is necessary and what understanding of sex (birth sex, “legal” sex, self-identification) is requested. A truly innovative company or agency, he suggests, would go further, with a written commitment to affirm the self-reported gender identity of all employees, patients, or customers.

"Small and seismic"

Davis begins the book with a recommendation that is both small and seismic: removing sex-classification markers from drivers’ licenses, passports, and birth certificates. If the goal is to ascertain identity and prevent fraud, he argues, there are more effective tools, such as fingerprints, face recognition technology, and security questions.

He applies the same test to sex-segregated bathrooms. If the purpose of a public restroom is to provide a safe, clean, somewhat private space in which to relieve oneself, then all-gender bathrooms would fulfill that aim without causing the anxiety, humiliation, and potential for harassment that happen every time a trans or gender-nonconforming person pushes open the door marked “men” or “women.”

ADA accommodations (ramps, elevators, automatic doors) benefit non-disabled people, such as parents with strollers or travelers dragging wheeled luggage. All-gender restrooms would help a range of users: the father taking his young daughter to the bathroom, the elderly man with a female caregiver.

For single-sex colleges or professional sports teams to strip sex classification from their practices is more complicated and more controversial. What about the longtime mission of women’s colleges to provide a supportive and ambitious educational environment for a historically excluded group? What about the physiological differences that can give male bodies a competitive edge on the playing field?

In both cases, Davis calmly returns to the gauge he believes should guide all sex-classification policies: Is there a compelling reason — not mere habit or tradition — to label and divide people by sex? Are current practices relevant to the organization’s goals, whether those are to foster a feminist campus, provide recreation and camaraderie to amateur athletes, or ensure fair play in competitive sports? Even in high-stakes realms — say, the Olympics — he suggests that measures of height, weight, and androgen (“male hormone”) levels would be more meaningful ways to sort out who may compete on which team.

The greatest strength of Beyond Trans is its reminder that there is nothing “natural” and not necessarily anything “reasonable” in sorting people by sex. Davis points out that such policies, though ubiquitous, “are material artifacts that were conceived and codified by people, and thus can be rewritten and overwritten by the same people or their successors.” It’s not a moment too soon to start editing.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman