Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Unburied treasures

‘Archaeology at the Site of the Museum of the American Revolution’ by Rebecca Yamin

Philadelphia’s bicentennial-era visitors' center never lived up to expectations, but it did one thing exceptionally well: it physically protected the past. Rebecca Yamin’s new book, Archaeology at the Site of the Museum of the American Revolution, digs deep beneath the ground-level structure that preserved brick privies, granite foundations, household castoffs, and tavern trash left by residents, shopkeepers, artisans, laborers, future mayors, and widows skirting the law.

All of this came to light in a 2014 archaeological dig at 3rd and Chestnut Streets, as the site was cleared to make way for the Museum of the American Revolution. Exploration revealed that the old visitors' center had shielded evidence of three centuries of people never mentioned in history books — until now.

In her book, Yamin describes what urban archaeologists, historians, and construction professionals found. Yamin, principal investigator for archaeological excavation and analysis at the site, describes the process of discovering “a veritable archaeological history of Philadelphia in microcosm…. Only rarely has archaeology revealed the evolution of a site from the very earliest days of the city to the middle of the twentieth century.”

Uncovering ordinary people

In 120 abundantly illustrated pages, Yamin conveys the challenge of urban archaeology, which traces unrecorded lives through found objects and public documents. It’s a specialization that heralds workaday people in the neighborhood, those who kept things going while the Founding Fathers declared independence and formed a nation — people like publisher Jesper Harding, button-maker George Lippincott, and enslaved servant James Oronoco Dexter.

Though no evidence was found of Native Americans on the site, two privies yielded early 18th-century artifacts, such as a cattle horn, bark fragments, and leather scraps from tanneries that stood here in the 1720s and ‘30s. The Garrigues/Smith privy contained marbles that probably belonged to the 10 children of Samuel and Mary Garrigues and dishes used by William Smith, whose sons closed his home after his death. That privy also held a tavern’s worth of drinking vessels, which researchers surmise came from the Three Tun Tavern across the street.

The privy, the punchbowl, and the ‘disorderly house’

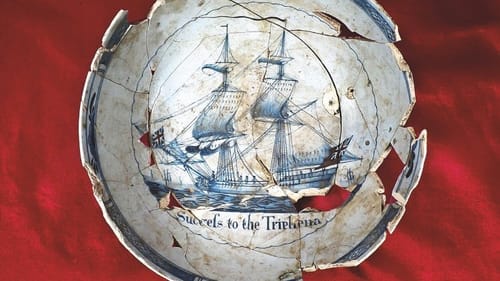

The Tryphena Bowl is one of the most exciting artifacts found on the site. Reassembled from pieces found in the privy of Mary and Benjamin Humphreys at 30 Carter’s Alley, the blue-and-white punchbowl, made in the 1760s, bears the image of a ship with the politically laden inscription “Success to the Tryphena,” which the book explains.

The Humphreys' privy also yielded enough liquor bottles, tankards, glasses, and jugs to lead the researchers to conclude that the Humphreys ran a drinking establishment in their dwelling. In 1783, Mary Humphreys was charged with operating a “disorderly house,” or unlicensed tavern, and spent time in the gaol and workhouse, presumably for that charge.

Carter’s Alley (later a street), was named for William Carter, one of four men to whom William Penn gave the original land grants for the site. Piercing the interior of the city block, the passage was accessible until the 1970s, when the National Park Service built the visitors' center. It gave archaeologists a spatial reference point.

The medical millionaire

The alley evolved to more commercial use as the 18th century passed into the 19th. Printers’ type was among the first and most abundant artifacts found, consistent with the fact that both the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Saturday Evening Post began publishing at 36 Carter’s Alley in the 1830s. Publishing was also one of the many industries occupying the Jayne Building, constructed in the 1850s by physician-entrepreneur Dr. David Jayne.

Jayne, who made patent medicines and published a medical almanac, was one of the city’s first millionaires and built a structure to match his ambition. The eight-story granite building, which ultimately consumed much of the block, was constructed with cast-iron columns and a roof that captured rainwater, enabling it to have running water and toilet facilities. The Jayne Building stood on Chestnut Street until 1958, when it was taken down to restore Independence National Historical Park to its colonial appearance.

Digging while we build

In urban areas, archaeology and construction often take place simultaneously, despite their seemingly opposite objectives and approaches. That was the case here: The excavation required by the National Park Service land transfer took place as the ground was being prepared for construction.

Day-to-day excavation on the site was directed by industrial archaeologist Tim Mancl. To find buried structures in an urban environment, Yamin writes, “we need the help of skilled construction workers, especially machine operators, to carefully scrape off the deep fill that covers anything that might be significant archaeologically…. If we see something … we ask the machine operator to stop digging so we can take a look…. This is not easy for anyone. It slows down the contractor’s work, and it puts the archaeologists under pressure to record information.”

In all, about 82,000 artifacts were found. Representing hundreds of individual lives, they restore to living memory people, places, and events that would otherwise have remained buried in the past.

On Saturday, January 26, from 1pm to 3pm, meet author Rebecca Yamin, who will sign copies of the book at the Museum of the American Revolution.

What, When, Where

Archaeology at the Site of the Museum of the American Revolution. By Rebecca Yamin. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2019. 152 pages, paperback; $19.95. Click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.