Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

An artist with Alzheimer's

What is the color of extinction?

The art of William C. Utermohlen

ROBERT ZALLER

“Do not go gentle into that good night,” says Dylan Thomas; “Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/ Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But what if the light is dying not from without but within--what if the capacity to protest, or even to understand what is under protest, is being eroded day by day, stealthily, inexorably, and irreversibly?

That was the dilemma faced by the artist William C. Utermohlen in 1995 when, at the age of 62, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Utermohlen, a Philadelphia native and a graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, had made his career in London. A portrait sketch from 1967, included in the small but shattering exhibit on display at the Philadelphia College of Physicians, shows a sensitive young man with thinning, receding hair and slightly protruding eyeballs. Two sheets from a suite of drawings on ten poems by Wilfred Owen, executed in 1994, find him still at the height of a considerable talent. Then his world collapsed.

Self-portraits without parallel

Utermohlen’s symptoms had already begun to manifest themselves when he received his fatal diagnosis. He made an immediate decision: As long as his faculties lasted, he would document his condition through his art. The result was a series of self-portraits— the last painted, or perhaps abandoned, in 2000— that have no parallel in the history of fine art, and that, indeed, compel us to rethink the boundaries of art itself.

The trope of the artist in old age-- Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Goya, Picasso-- is familiar , but in the works of these masters there is no question of artistic decline, even as they portray bodily decay. The case of Willem de Kooning, who went on painting after the onset of dementia, is more problematic, but de Kooning wasn’t a representational painter and, although critics have debated whether or to what extent his late work reflected his condition, he didn’t attempt to portray it as such. Utermohlen’s case, as far as I know, is unique.

The first portrait in the series is entitled, with terrible irony, “Blue Skies” (1995). It depicts the painter seated at a table under an open skylight. His left hand grips the edge of the table; his right one holds a coffee mug. The sky above him is a patch of undifferentiated dark blue, as is the base of the painting beneath him. You understand that this blue is what will engulf him; it is the color of his extinction.

'I cnot wright. I can not redd.'

Within a year, some of Utermohlen’s cognitive faculties had deteriorated markedly. There are two sheets from a notebook dated 1996; on one, he laboriously attempts to write his name; on the other, he writes simply, “I cnot wright. I cn not redd.” Yet his plastic ability remains intact. A “Self-Portrait with Easel (Yellow and Brown)” shows Utermohlen staring out of the frame of his easel as if from a window. Is he telling us that he has retreated into a final refuge, that of his art, or that it is only through that art that he can still look out at the world? It is a sophisticated question, and, although the style of the painting is simplified, there seems no loss of competence or control.

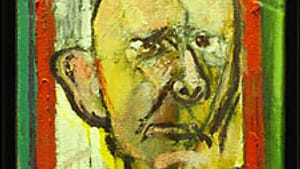

However, in another 1996 work, “Self-Portrait (Red),” we confront the face of a man suddenly and deeply old, with what looks like a superimposed mask or skull on the sunken features; and in two watercolors, “Mask I” and “Mask II,” the theme is taken up directly: the first mask represents a head in the form of a fired ceramic, and the second a Klee-like red image on a stilt of six green stripes, like a decapitated head on spikes. Finally from 1996, “Broken Figure” depicts a doll-like figure with what appears to be an easel, at all odds a geometric form whose cohesion contrasts starkly with the figure’s splayed limbs and lolling head.

Terror in the eyes

Utermohlen’s symbolic code is clear: The abiding form of the easel represents the art he can still command, while the portraits record not only his sense of a progressive loss of other forms of cognition and control, but of self-image, of selfhood itself. The eyes, always prominent, are widened with confusion and terror. Determined to see and unable to accept, he can record only estrangement: He must paint himself as someone else.

In “Self-Portrait with Saw” (1997), the eyes are drifting, the mouth hangs open, and terror suffuses the entire face, while the saw that hangs beside the artist suggests the dreadful edge he approaches, or the possible violence that might deliver him from it. By 1998, the head is free-floating, the features distorted. The last finished portrait is monstrous— a large nose, no eyes, skewed mouth, flared ear— and, finally, there is a partially effaced sphere whose features can be vaguely glimpsed, half-enclosed in a green frame. It is still an assertion; it is still art.

But is he what he represents himself?

To what degree can we attribute to Utermohlen the intention we read in this body of work? What is it that he actually saw in himself? Who, in the end, was he? “Outsider” art, and the art of the insane, poses this question for us as well; but the mad, with their typically labyrinthine patterns and their compulsive need to cover every square inch of canvas or paper, present us with something that is by definition self-alienated, at least by our standards of normality. Their art is aberrant, or so we have decided, and speaks to us on different terms. But Utermohlen was trying to the last to communicate in the language he still shared with us, or what remained of it. We are forced to accept it as such, without knowing where we ourselves are filling in gaps, patching up the narrative, trying to make the communication whole. In other words, we are forced to make William Utermohlen fully human to the end— perhaps the legacy he was trying to leave us.

It is impossible not to speculate whether Utermohlen is what he represents himself to be; in short, whether these works, with their nod to Klee here and to Bacon there, are perhaps a fraud, or the product of another hand. His tragedy is documented, however, and his work was given to the London Neurological Hospital. What authenticates his art is precisely what leads one to doubt it: the lucidity of its terror. Judge for yourself.

The art of William C. Utermohlen

ROBERT ZALLER

“Do not go gentle into that good night,” says Dylan Thomas; “Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/ Rage, rage against the dying of the light.” But what if the light is dying not from without but within--what if the capacity to protest, or even to understand what is under protest, is being eroded day by day, stealthily, inexorably, and irreversibly?

That was the dilemma faced by the artist William C. Utermohlen in 1995 when, at the age of 62, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Utermohlen, a Philadelphia native and a graduate of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, had made his career in London. A portrait sketch from 1967, included in the small but shattering exhibit on display at the Philadelphia College of Physicians, shows a sensitive young man with thinning, receding hair and slightly protruding eyeballs. Two sheets from a suite of drawings on ten poems by Wilfred Owen, executed in 1994, find him still at the height of a considerable talent. Then his world collapsed.

Self-portraits without parallel

Utermohlen’s symptoms had already begun to manifest themselves when he received his fatal diagnosis. He made an immediate decision: As long as his faculties lasted, he would document his condition through his art. The result was a series of self-portraits— the last painted, or perhaps abandoned, in 2000— that have no parallel in the history of fine art, and that, indeed, compel us to rethink the boundaries of art itself.

The trope of the artist in old age-- Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Goya, Picasso-- is familiar , but in the works of these masters there is no question of artistic decline, even as they portray bodily decay. The case of Willem de Kooning, who went on painting after the onset of dementia, is more problematic, but de Kooning wasn’t a representational painter and, although critics have debated whether or to what extent his late work reflected his condition, he didn’t attempt to portray it as such. Utermohlen’s case, as far as I know, is unique.

The first portrait in the series is entitled, with terrible irony, “Blue Skies” (1995). It depicts the painter seated at a table under an open skylight. His left hand grips the edge of the table; his right one holds a coffee mug. The sky above him is a patch of undifferentiated dark blue, as is the base of the painting beneath him. You understand that this blue is what will engulf him; it is the color of his extinction.

'I cnot wright. I can not redd.'

Within a year, some of Utermohlen’s cognitive faculties had deteriorated markedly. There are two sheets from a notebook dated 1996; on one, he laboriously attempts to write his name; on the other, he writes simply, “I cnot wright. I cn not redd.” Yet his plastic ability remains intact. A “Self-Portrait with Easel (Yellow and Brown)” shows Utermohlen staring out of the frame of his easel as if from a window. Is he telling us that he has retreated into a final refuge, that of his art, or that it is only through that art that he can still look out at the world? It is a sophisticated question, and, although the style of the painting is simplified, there seems no loss of competence or control.

However, in another 1996 work, “Self-Portrait (Red),” we confront the face of a man suddenly and deeply old, with what looks like a superimposed mask or skull on the sunken features; and in two watercolors, “Mask I” and “Mask II,” the theme is taken up directly: the first mask represents a head in the form of a fired ceramic, and the second a Klee-like red image on a stilt of six green stripes, like a decapitated head on spikes. Finally from 1996, “Broken Figure” depicts a doll-like figure with what appears to be an easel, at all odds a geometric form whose cohesion contrasts starkly with the figure’s splayed limbs and lolling head.

Terror in the eyes

Utermohlen’s symbolic code is clear: The abiding form of the easel represents the art he can still command, while the portraits record not only his sense of a progressive loss of other forms of cognition and control, but of self-image, of selfhood itself. The eyes, always prominent, are widened with confusion and terror. Determined to see and unable to accept, he can record only estrangement: He must paint himself as someone else.

In “Self-Portrait with Saw” (1997), the eyes are drifting, the mouth hangs open, and terror suffuses the entire face, while the saw that hangs beside the artist suggests the dreadful edge he approaches, or the possible violence that might deliver him from it. By 1998, the head is free-floating, the features distorted. The last finished portrait is monstrous— a large nose, no eyes, skewed mouth, flared ear— and, finally, there is a partially effaced sphere whose features can be vaguely glimpsed, half-enclosed in a green frame. It is still an assertion; it is still art.

But is he what he represents himself?

To what degree can we attribute to Utermohlen the intention we read in this body of work? What is it that he actually saw in himself? Who, in the end, was he? “Outsider” art, and the art of the insane, poses this question for us as well; but the mad, with their typically labyrinthine patterns and their compulsive need to cover every square inch of canvas or paper, present us with something that is by definition self-alienated, at least by our standards of normality. Their art is aberrant, or so we have decided, and speaks to us on different terms. But Utermohlen was trying to the last to communicate in the language he still shared with us, or what remained of it. We are forced to accept it as such, without knowing where we ourselves are filling in gaps, patching up the narrative, trying to make the communication whole. In other words, we are forced to make William Utermohlen fully human to the end— perhaps the legacy he was trying to leave us.

It is impossible not to speculate whether Utermohlen is what he represents himself to be; in short, whether these works, with their nod to Klee here and to Bacon there, are perhaps a fraud, or the product of another hand. His tragedy is documented, however, and his work was given to the London Neurological Hospital. What authenticates his art is precisely what leads one to doubt it: the lucidity of its terror. Judge for yourself.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller